By: Rick August

Social policy refers to the aspects of public policy that affect the distribution of income and wealth within a community, the relationships between people in communities, the well-being of individuals and family units, and the relative security or risk that individual citizens experience in their relationship to the economy. Social policy is generally considered to include policy and programs dealing with Income Security and income redistribution, as well as health, Education, and social services that support individuals’ quality of life in communities. Saskatchewan, in the past half-century, has frequently been an innovator in this aspect of public policy development.

It is common to make a distinction between social and economic policy, the latter being broadly concerned with wealth creation; but the two are very closely linked. Economic activity provides the material means to support social programs, while social policy helps ensure the human resource base and stability of social relations that are preconditions to a healthy economy. The most effective social policy is developed with strong reference to economic issues and relations, and vice versa. Social policy can have a number of purposes: it can redistribute resources among individuals or family units to ensure that “social minimum” standards of living are maintained; it can influence or modify relationships among citizens to make a community more cohesive and secure; it can also shape peoples’ social or economic behaviours, or mediate the impacts of market forces and social trends on individuals and families.

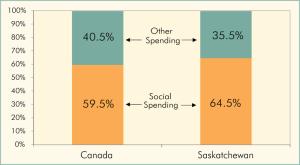

In simpler societies of the past, social matters were resolved within families, through informal responses from communities, or through voluntary charitable actions. In Saskatchewan, as in other maturing communities, economic and social relations became more complex as the economy developed, and people became more mobile than they were at the time of the province’s formation. Families or communities gradually lost the capacity to deal with the range of social risks their members encountered. To bridge this gap, citizens have asked their governments to organize social policy solutions in order to provide protections that families and communities cannot adequately provide. At the time of Saskatchewan’s formation, government’s social responsibilities were relatively limited; but citizens’ expectations have increased significantly over time: in the current budgets of both Saskatchewan and Canada, social programs now represent over half of public expenditures.

Some social programs and policies have been in place so long that people tend to take them for granted, but social programs reflect collective choices and priorities that may change over time. The local “relief” programs and Labour camps that were considered adequate unemployment protection in the early 1930s, for example, were eventually replaced by unemployment insurance and Social Assistance. Views on these programs in turn have evolved as public values change and as governments acquire experience of income security issues. The expansion of social policy is one of the factors that have increased the relative size of the public sector relative to the private sector of the economy, but social policy is not necessarily intended to replace or compete with the market economy. People who live in market economies like Saskatchewan’s enjoy freedom of choice and personal economic opportunities that may not be available in more structured economic environments. By reducing social risks, social policy can stabilize the economy, reduce social conflicts, and help secure a stable, healthy and motivated population that is able to participate in, and benefit from, a market economy. (See Figure 1.)

Every society makes choices, through its social policies, about the balance between individual and social responsibility. Some believe that Saskatchewan people rely more than most on government to provide collective responses to social issues. It can be argued that there are circumstances specific to Saskatchewan that may have served to increase expectations on government: the land area is large, the population sparse, and the climate extreme; the province’s former strong reliance on commodity production also made it more vulnerable than most to economic forces.

The province is also, in historical terms, a new and still developing entity. Descendants of European settlers and more recent arrivals from around the world still struggle to forge with the Aboriginal population the sense of being “one people,” with a shared vision for the future. Social policy has historically been influenced very strongly by ideology, with the result that there are varying degrees of support among the public for particular social programs. Over time, social policy practitioners have struggled to replace ideological assumptions with more scientific, evidence-based approaches appropriate to an emerging behavioural science. To the extent that social policy development becomes more scientific, its outcomes will be more predictable, so that better choices can be made about public investment. A critical analysis of current social policies would reveal many flaws, some of them quite serious. Given the scale of government spending on social programs and their importance to the lives of Saskatchewan people, better social policy is an important goal for the future.

Governments at the federal, provincial or local level formulate most social policy. While they have the principal role in establishing social policy and often in funding social programs, the actual implementation of social policy may occur in a number of ways, often involving non-government stakeholders. Some social policies and programs are implemented directly by government through programs and services delivered by public servants. In Saskatchewan certain social services such as child protection functions are organized this way. Government may also pay a private business or individual to deliver a social program directly to citizens. Some residential services for adults requiring special care, for example, are operated by private individuals or corporations, while private businesses are active in areas such as disability supports.

Other services may be delivered by agencies or institutions outside of government, but subject to varying degrees of government control or influence exercised through funding relationships. These so-called “third party” social policy agents can range from small local community social service organizations to large, complex and long-standing institutions like school boards or regional health authorities. Often the delivery agents have mixed sources of funding from levels of government and non-government sources. The role of non-government and quasi-government organizations in the delivery of social policy has increased over the last three decades, while government’s direct role has narrowed. Some social policies are implemented by regulating markets or relations between citizens, rather than by providing social benefits or services. An example of this type of policy would be labour laws and regulations that set minimum standards for wages and employment conditions. By influencing the behaviour of employers towards their employees, these public policy measures help society maintain minimum work and living standards among the significant proportion of the population that makes a living through paid employment.

Governments may also transfer funds directly to citizens to help them buy the supports or services they need from existing private or public markets. A significant proportion of tax revenue is spent on such transfers to individuals. Federal public pensions that help ensure that citizens are not destitute in old age are paid to millions of older Canadians; federal and provincial child benefits are paid to over 80% of all families with Children. There are also provincial programs that transfer funds to individuals: social assistance, for example, provides last-resort income support to individuals and families, while the Saskatchewan Employment Supplement helps low-income parents offset child-related costs of working. (See Figures 2 and 3.)

When Canada’s first constitution, the British North America Act, was adopted by the British Parliament in 1867—with Saskatchewan’s formation nearly four decades in the future—governments had limited involvement in the social affairs of citizens. The constitution reflected a division of responsibilities between the federal and provincial levels of government, including social policy responsibilities. The Act assigned provinces jurisdiction over the “Establishment, Maintenance, and Management of hospitals, Asylums, Charities, and Eleemosynary Institutions in and for the Province, other than Marine Hospitals”—roughly the extent of social policy in the middle of the 19th century. Courts have interpreted this clause in modern terms to mean that provinces have jurisdiction over social policy, except where powers are specifically granted to the federal government. The same division of powers was preserved when the constitution was made an act of Canadian rather than British law in 1982. The constitution does not necessarily preclude the federal government acting within provincial jurisdiction, but it must do so with the consent of the province or provinces concerned.

There have been circumstances in Canada’s history that have resulted in an expansion of federal social powers through constitutional amendments. Federal unemployment insurance and pensions, for example, both came about by virtue of amendments to the constitution, in 1940 and 1951 respectively, with unanimous consent of the provinces. The boundaries between federal and provincial social responsibilities, clear enough in theory, are somewhat unclear in practice. The federal government has responsibility for the management of the national economy, and therefore has substantial control over the conditions that affect demand for social programs. Provinces also claim that the powers of Taxation set out in the constitution have not expanded along with the wider responsibilities of provincial governments for social policy. The federal government has developed mechanisms to provide funding to provincial and territorial social programs—but at the expense of tensions, and occasionally conflicts, over the social policy independence of provincial jurisdictions.

A number of models have emerged for federal involvement in provincial and territorial social programs. When Saskatchewan municipalities and the provincial government were under severe financial pressure from unemployment relief costs during the Depression, the federal government provided ad hoc financial support for about three years. There have been mechanisms for cost-sharing programs between governments, such as the Canada Assistance Plan that existed from 1966 to 1995. More recently the federal government has opted for less open-ended block grants to provinces for health and social services, with varying degrees of conditions attached. These federal transfers are significant revenue sources for the provinces and territories, totaling $21.8 billion in 2003–04 to support health, post-secondary education, social assistance, and social services. One further model of social policy development is implemented through strategic co-operation among governments. This has been employed only once to date, in the development of the National Child Benefit, Canada’s first major new national social program since the 1960s. In this case, the federal government and all provinces and territories except Québec agreed to work together to reduce child and family poverty, and also agreed on a strategy of providing both child benefits and employment support to parents.

Under the National Child Benefit, the federal government created a new benefit that was intended to replace basic benefits for children in provincial social assistance. The new child benefit was intended to improve work incentives by equalizing child benefits between welfare and working poor families. Where the new federal benefit created costs savings for provinces, these are reinvested in further supports for low-income families. Saskatchewan has an employment-oriented policy agenda for fighting family poverty which is very consistent with the National Child Benefit strategy, and the province was therefore a strong advocate for the initiative, which came about as a result of direction from provincial Premiers and the Prime Minister. The province’s National Child Benefit reinvestments include a suite of programs called Building Independence that encourage parents to increase their earnings and improve their families’ living standards. The National Child Benefit served as the model for a more permanent protocol for co-operation between the federal government and the provinces and territories in social policy. In 1999 all Canadian jurisdictions except Québec entered into the Social Union Framework Agreement (SUFA); the longer-term effect of SUFA on federal-provincial relations, if any, is still unknown.

Municipal governments in Saskatchewan currently have a somewhat more limited role in social policy and programs, although that was not the case in years past. As social policy developed away from a base in family and charity, the first public social programs were municipal or governed by local bodies. At the onset of the Depression of the 1930s, local governments in Saskatchewan were responsible for both income support and health programming. While education remains, in part, locally governed and financed, responsibility for health, income security and social services has migrated, in stages, to the provincial government, which in some cases delegates implementation responsibility back to local or regional bodies. One area of social programming where municipalities continue to play a role, direct and indirect, is housing: some municipalities are active with other partners in development of public, private and non-profit housing assets, particularly for low-income people. Municipal governments have powers to regulate land assembly and Land Use, which in turn affect the supply, quality, and cost of housing. Local governments also have a strong influence over neighbourhood and community issues that are important to peoples’ everyday lives.

Social outcomes are also influenced by non-government organizations operating at various levels and with a range of mandates. National Policy institutes like the Caledon Institute or Canadian Policy Research Networks are primarily focused on social policy analysis, while other organizations such as the Fraser Institute or the C.D. Howe Institute address a range of public policy issues. The Saskatchewan Institute for Public Policy, a co-operative endeavour of the universities and the provincial government, offers Saskatchewan perspectives on social and other public policy issues. Professional organizations also influence social policy outcomes, based both on their interests as professions and their ethical frameworks. Various medical professions are very influential in the form and content of health services. Organizations like the Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers include advocacy around social issues as an element of ethical conduct in the profession. There are also a large number of community-based organizations that influence social outcomes, either by providing services or by helping finance aspects of social programs. The activities and policies of community-based organizations represent, in one sense, a local response to community needs, and a local aspect to social policy development. In 2003 there were over 1,400 voluntary and non-profit organizations in Saskatchewan—active in education, health or social services.

Aboriginal communities and organizations are also increasingly active in social policy and programs. In Saskatchewan, both First Nations and Métis organizations provide or fund a variety of social services, and have expressed interest in greater involvement in social policy development. Some of these organizations, like the First Nations child and family service agencies, operate under provincial legal authority, while others are independent non-profit organizations that receive funding or fees for service from a variety of sources. There is also an international dimension to social policy, whose standards can be an issue in international relations; governments and international organizations sometimes attempt to influence social policy in other countries by trade policy, aid, or even sanctions. Social standards can also be an issue in trade pacts like the North American Free Trade Agreement, in part because firms operating in different social environments will incur different costs that will affect competitiveness. Social standards can also be influenced by international bodies like the United Nations, the World Trade Organization, or the International Monetary Fund. The world continues to move towards a greater reliance on international trade, greater movement of capital and labour between countries, and more open national economies. The international organizations that now exist, most of which were created after World War II, face new challenges, not only to mediate national interests, but also to create inclusive debate on policy issues.

There are three basic approaches that governments use to achieve social policy outcomes: they can establish and operate public services, either directly or through arm’s-length organizations; they may provide funding to non-governmental organizations to offer services to citizens; they may also establish a direct relationship with citizens, not mediated by service providers, to resource a particular outcome. In Saskatchewan, social assistance and child welfare systems are examples of direct government services. Health services and primary and secondary education services are provided by service sectors closely aligned with and funded by governments. In recent years there has been a trend for government to reduce its direct role in service provision, and for allied service systems to assume greater autonomy and accountability for effectiveness of their services.

Since the 1970s, private and non-profit service organizations have increased their role in delivery of social policy outcomes. Delivery agents can range from private enterprises such as personal care homes, private preschools and family child care providers, to a wide range of services provided by non-profit organizations. Local providers, private or non-profit, can usually claim the advantage of responsiveness to community needs. Because the locally based service delivery system has expanded so quickly, however, concerns are emerging about coordination and effectiveness of public investment in this sector.

Governments also sometimes rely on programs that provide financial resources directly to citizens, who in turn use these resources to help them buy goods or services in local markets. Examples are the development of the federal Canada Child Tax Benefit, which provides a cash benefit each month to all lower-income parents in Canada for their children’s needs, and the Saskatchewan Employment Supplement, which helps low-income working parents in Saskatchewan with child care and other employment-related costs.

In the view of many analysts, the depth and breadth of social policy is a function of the level of economic development and organization of a society. In the 19th century, when present-day Saskatchewan was part of the North-West Territories, Canada was primarily an agricultural and resource-based nation, with most economic activity associated with producing crops and primary products for export. In the last half of the 19th century, as Canada’s economy and society became more complex, charitable institutions such as hospitals and asylums expanded, and public funding of such institutions became more common. Social programs emerged to address problems and issues that individuals and families were poorly equipped to handle on their own. One of the first examples of broad-based social programming was the organization of schools, with its policies of compulsory schooling. This reflected a recognition that children would need more education than their parents had, and that families could not provide the level of education that coming generations of citizens would need to prosper in a developing society.

The growth of population centres and labour markets led as well to other public policy responses such as public health laws and greater regulation of employment conditions. On a national level, one of the first modern social programs that emerged—around the time of World War I in most of the country, but later in Saskatchewan—was workers’ compensation. If social policy reflects the complexity of society, it is also often shaped by great events. World War I, for example, and the recession and social unrest that followed it, set in motion forces that resulted in several new, if rudimentary, social programs. Saskatchewan introduced mothers’ allowances in 1916, and modest pensions for the elderly and infirm in the 1920s. The Depression, which was particularly severe and prolonged in Saskatchewan, ushered in a more interventionist period in income security, which would lead to programs such as unemployment insurance and social assistance.

World War II ended the Depression and raised the general level of attention to and interest in greater social justice as a goal for modern democratic governments. Two decades of economic expansion after the war were capped by a very rapid period of expansion of social programs in the 1960s and early 1970s. Saskatchewan pioneered a publicly funded Health Care program that became a national model in 1966. In the same year the federal government launched the Canada Pension Plan, and the Guaranteed Income Supplement for seniors. The Canada Assistance Plan and the Saskatchewan Assistance Plan of 1966 improved income support and social services. National unemployment insurance was expanded and enriched significantly in 1971.

Events since the early 1970s, however, have checked the headlong growth of social programs. Economic events like the oil crises of the mid-1970s at first were viewed in Keynesian terms, as down-cycles to be buffered by counter-cyclical government spending. In fact, these events were part of a long-term trend, eventually known as “globalization,” which would result in significant structural changes to economies and labour markets, and increased demand pressure for the major social supports that are sensitive to economic conditions. Early instincts to spend or borrow their way out of recessions set governments on a course of deficit financing and debt that placed even greater pressure on social programs than external events did. Provincial governments, including Saskatchewan’s, implemented rigorous deficit and debt reduction measures in the early 1990s; the federal government did the same, culminating with major social program funding cuts in the 1995 federal budget. Since that time, most governments have established reasonably stable finances, and social policy development is moving forward once again, albeit rather cautiously.

As a young behavioural science, social policy still generates a good deal of debate and discussion. To a great extent, public authorities are still experimenting and learning how to address social issues constructively and to shape human behaviour in ways that serve the interests of the individuals affected and of communities as a whole. Social policy debates play out along a number of dimensions, depending on the opinion or belief system of the observer, or the evidence available to inform judgments. A non-exhaustive review of these dimensions might include some of the following, many of which are conceptually linked or related.

In the period of initial European settlement and the more agriculturally dominated era of Saskatchewan’s history, governments were active in enforcing boundaries on individual citizens’ behaviour relative to others, but took less responsibility for assuring the well-being of private citizens. The assumption was that such welfare issues were private matters for individuals, families, churches and charities to address. The situation today is quite different. Measures to protect the well-being of citizens take up the majority of the budgets of modern governments, which are themselves much larger in scope than in the 19th century. Most citizens have come to expect that the state will enforce a minimum living standard, provide basic education, and ensure that health care needs are met. Some view government as having a responsibility to repair any major deficiency in citizens’ lives, be it lack of housing, low income, or other problem.

The historic peak of the era of public responsibility was the early 1970s, the last period of significant social program expansion. Since that time, the public has lost a degree of confidence in government’s ability to solve problems for citizens. The cost of social protection was one of the factors which generated government debt and deficits that necessitated cutbacks in the early 1990s. Evidence has also emerged of negative outcomes associated with very high degrees of social protection, particularly dependency and loss of personal capacity for independence, when programs are not oriented toward active roles in the economy. At the root of the “public versus private” debate is the concept of citizenship: those who support a more interventionist state see government as the means to redress inequities and provide personal security; those who lean towards a less active state see citizens as having more personal responsibility for managing their own lives and solving their own problems.

Another aspect of the debate over the role of the state in social policy has to do with how government is expected to achieve social outcomes. Perspectives on the means for achieving social policy outcomes are changing over time.

In much of the post-war period of social program expansion, government was seen as directly acting to provide goods and services to citizens to produce social outcomes. This is still the basis of much social policy. However, an alternative view has emerged in some areas, particularly in income security, where cash entitlements to citizens by the state have been criticized as contributing to dependency. An example of this debate concerns social assistance (commonly called “welfare”), which has always been a controversial program with the public. Designed to be a “last-resort” income source for people with no other means, modern social assistance programs evolved out of ad hoc government assistance to people in economic distress. Over time, some analysts came to view welfare as a solution to poverty, based on a simple premise: if citizens lack money, government will provide it, regardless of the reason for the need. The preamble to the 1966 Canada Assistance Plan actually envisioned a society without poverty as a result of such welfare measures.

As history proves, social assistance has not eliminated poverty. In fact, some would argue that welfare actually reinforces poverty by drawing low-income people out of the labour market. Critics have argued that the premise of welfare should change, from benefits as a source of income security to cash or service supports that should explicitly encourage employment and self-sufficiency outcomes. In this example, the proposed shift would be from government providing a citizen with income, to government facilitating citizens to meet their own needs through paid employment. A recent study by the Canadian research firm Pollara Inc. indicates that a shift in public opinion is taking place about the role of government. In 1989, 51% of Canadians thought that government’s role was to “solve problems and protect people from adversity,” and 28% thought it was to “help people equip themselves to solve their own problems.” A follow-up survey in 2001 indicated that by that time only 31% thought government should solve problems, and 48% saw government in a facilitative role (see Figure 4). The notion of facilitative policies places a burden on governments to develop more sophisticated and evidence-based approaches, since facilitation requires the policy to influence behaviours—which is more complex than simply meeting needs.

Closely related to the “provider or facilitator” debate is the issue of the tactics used by social policy to achieve the desired outcomes. Prescriptive interventions by government use relatively direct means to ensure a given outcome: provision of goods or services meeting certain standards, or regulations that govern the behaviour of individuals, businesses or institutions. Enabling tactics use government authority and resources more indirectly to create conditions that encourage desirable outcomes; Shlomo Angel (2000) describes enabling social policy as setting boundaries, providing support, and relinquishing control of the detailed process of implementation. An example of prescriptive social policy in Saskatchewan is licensed child care: the government prescribes the model through funding rules and regulations, funds a variety of agencies to deliver the service, and subsidizes lower-income parents if they use that form of child care service. A more enabling approach might allow for parent choice among approved child care options, and the use of subsidies to increase parents’ economic leverage to increase care quality.

As in other aspects of social policy, public opinion has shifted over time. In the post-war growth period the public had a relatively strong faith in the capacity of governments to shape outcomes by regulation and other prescriptive intervention. The principal failings of prescriptive policies arise from the inexactness of social policy—in effect, the unlikelihood that government planners or elected representatives can accurately predict the measures that will achieve desired outcomes in advance. Prescription also reduces consumer choice, sometimes without a strong evidence base to justify such restriction. Enabling policies, on the other hand, entail more risk for public authorities because they rely on an appropriate response from citizens, and in some cases markets. Sometimes more time is required to effect a change, since the policy depends on a behavioural response of citizens. Governments are also sometimes reluctant to surrender direct control of outcomes. Proponents argue, on the other hand, that the outcomes are more consistent with the intent of policy because citizens’ resources and motivations are contributed to shaping outcomes.

There is considerable debate between those who think social policy’s goal should be to ensure that a person’s unmet needs are satisfied, regardless of circumstances or behaviour, and those who focus on supports that promote self-sufficiency. Those who favour a security focus argue that social policy’s principal role is to redistribute resources (goods, services, income) within society to ensure that all citizens have a more equal standard of living. Those who favour self-sufficiency argue that unconditional entitlements become unaffordable because demand grows over time, and that entitlements can undermine incentives for people to manage their own lives and solve their own problems. The long-term best interests of citizens, proponents would argue, are served by their capacity for independence. While a self-sufficiency framework does not preclude public support of individuals, it suggests that support should be conditional and framed so as to encourage self-sufficient behaviours.

One critique that has emerged of post-war “welfare state” programs is that these, by providing unconditionally for citizens’ needs, have encouraged and expanded dependence on government. In the long run, since government is financed by the economic activity of citizens, policies that discourage employment, enterprise and self-support, it is argued, are unsustainable and unhealthy, both for society and its members. Trends in social assistance are often cited to support this critique. In Saskatchewan, for example, social assistance was consolidated under new federal and provincial legislation in 1966, putting into place a new and more unconditional welfare regime. Although applicants were expected to explore work or other options for self-support, financial assistance was basically a right for those who could establish need, regardless of the circumstances. Citizens in need were given resources that addressed their immediate income situation, but very little was done to support economic rehabilitation.

In the quarter-century following implementation of this approach, social assistance use increased by about 180%; whereas a welfare caseload in the 1960s consisted of people unable to work, by the early 1990s a typical welfare recipient was a working-age single mother. While most would acknowledge other factors than program design in this trend, it is also generally agreed that economic dependency, particularly of working-age adults, is undesirable for both the dependent person and society as a whole. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a policy body whose membership consists of industrialized countries with developed social security systems, has been a forceful critic of passive social policies and their negative long-term impacts on the lives of lower-income peoples (OECD, 1988, 1994). The OECD promotes what it calls “active” social policies in their place. The active/passive program critique formed part of the basis for unemployment insurance reforms in Canada in the 1990s; it has informed, to some degree, initiatives like Saskatchewan’s Building Independence programs, designed to fight poverty by helping low-income people to remain in the work force.

Few would argue, in principle, with the maxim that prevention is better than cure—in social policy as in everything else. Since people have different views on the role of government, however, there are also differing views on the degree to which social policy should proactively shape behaviours, or simply react to problems that emerge. This debate, for example, would oppose social assistance as a last-resort response to income need, on the one hand, to income redistribution programs or an employment policy, on the other hand. Similarly, investment in acute medical treatment models in health care is sometimes contrasted to “population health” approaches intended to reduce demand for treatment services. In practice, governments still gravitate to a surprising degree towards short-term, residual responses—despite evidence that more structural, long-term policies provide better value for taxpayers’ money. Residual responses may provide more limited benefits, but they are immediate, relatively easy to identify, and outcomes can be more readily attributed to specific actions than some longer-term structural solutions.

Structural, institutional or preventive strategies, on the other hand, can often demonstrate their benefit in theory, but are quite hard to achieve in practice. Their rather abstract promise of benefits must compete with immediate priorities for service responses to existing demand: while research may support, for example, a population health strategy, headlines still stress surgical waiting lists. There is much greater benefit, to citizens and society, from an employment strategy to prevent economic marginalization; but most social advocacy in this area is still directed towards issues concerning short-term welfare. Another factor creating resistance to structural change is the vested interest that inevitably develops in existing program models. Service providers’ interest in the status quo is often very strong, and much more focussed in opposition to change than are the more diffuse forces in favour of change. Service consumers also tend to defend the status quo as preferable to the uncertainties of change. In a province and country with four- to five-year electoral cycles, it can be difficult to convince elected representatives to choose long-term change over short-term benefit. History suggests that the pressures of crisis situations are sometimes needed to force consensus on structural change. Examples of structural change in social programs are in fact relatively rare. On a national level, the most recent major example would be the National Child Benefit: in its simplest terms, it is a re-engineering of the structure of benefits for children in order to make employment more attractive for parents; it has also facilitated major changes to Saskatchewan income support and employment programs to support employment outcomes for low-income parents.

Differences of opinion exist as to whether the fundamental goal of social policy should be equality or equity among citizens. The distinction is a subtle but important one: equality arguments favour policies that try to assure more equivalent life outcomes, while equity policies do not attempt to modify outcomes directly, but rather seek to increase fairness in conditions that facilitate social outcomes. To some extent the debate is a false one, as neither perspective is really achievable in absolute terms. Those who favour greater equality might for example set an ideal of complete income equality across a society, or equal health outcomes; these goals, however, are not practically achievable, even in extremely regulated and regimented societies. Equity arguments are more concerned with opportunity: social policy operates through real people who are remarkably variable in their outlook, personal capacities, motivations and adaptabilities. Some believe that, because no public intervention can guarantee outcomes, the best approach is to focus on conditions that support the desired outcomes, thus increasing the likelihood that positive life outcomes such as good health, or secure and rewarding employment, will result.

An important development in recent years, in all public policy, but particularly in social policy, has been the emergence of a critical perspective on political or ideological approaches, and a bias towards outcomes-based analysis, in both the evaluation of existing measures and the development of business cases for new initiatives. An outcomes orientation is also intended to replace program performance measurement by throughputs—dollars spent, consumers served, etc.—rather than the actual effect of the program relative to its original intent. If only throughputs are considered, a program can appear to perform adequately, but may not actually achieve its goals. Outcomes orientation encourages organizations to engage to a greater extent in strategic planning, a process by which an organization articulates a vision that expresses the most basic intent of its activities. Using the vision as a reference point, the strategic plan lays out values the organization wants to adhere to, principles to be applied in finding solutions to problems, goals that orient the organization’s work, and measurable objectives around which an action plan can be developed to move towards achieving the vision.

The strategic plan makes the purpose and plan of an organization much more explicit. It therefore acts as a guide to management and governance. A strategic plan also provides the basis for more rigorous performance management, since the indicators of success or failure have been identified for comparison over time with actual outcomes. Almost all public authorities now engage in strategic planning and performance management. One positive outcome has been a renewed emphasis on developing a knowledge base in social policy, and more rigorous approaches to program evaluation. Improving the knowledge base for social policy will be a gradual, long-term process reflecting the complexity, and sometimes unpredictability, of human behaviour.

It is sometimes assumed that the funding, financing or resourcing of social policy measures is a matter for governments. In reality, almost all social policy relies at least in part on mixed resources of individuals, governments, labour markets, voluntary organizations and the consumers of service themselves. Governments involve themselves in social programs in a number of ways. The approach in which government provides services and funds them through tax revenue has sometimes been called the “social utility” model; the closest example to this in present-day Saskatchewan would be the fully publicly insured portions of the health care system, which are financed almost entirely by federal and provincial government contributions. However, even this system represents a mixed approach, as evidenced by the various charitable organizations that raise funds for health services, a growing corporate role in capital facilities development, and an increasing range of user charges. The elementary and secondary education systems are largely funded by the provincial government and local property taxpayers, but families are still expected to contribute school supplies, and some school-related activities levy fees on parents for participation.

Another form of social program organization and finance is referred to as “social insurance”: “insurance” because it involves premiums or contributions by individuals to buy protection against risks, and “social” because the insurance program is managed by government. The role of government is to force pooling of risks in a way that private insurance would not. For example, Canada’s Employment Insurance program relies on cross-subsidies to those at greater risk of unemployment, with premiums from those at lesser risk; such mandatory programs also ensure that high-risk people can be insured, which may not be the case in private insurance. Another form of social insurance program is the Canada Pension Plan. By levying a payroll tax on earnings, the Canada Pension Plan forces citizens to save for retirement during their working years. The funds that people contribute are managed and invested under rules and procedures that provide more security than most private investments. The Canada Pension Plan, along with the universal Old Age Security pension, private pensions, and the income-tested Guaranteed Income Supplement, form a system that has sharply reduced seniors’ poverty since the 1960s.

Some social programs and services are organized on a community basis, with mixed funding from governments, service consumers and charitable sources. Sometimes these are services that operate with local autonomy within a philosophical or religious framework provided by a provincial or national organization. Other community-based services are united by ideology or focused social goal; still others are simply responses to specific priorities of local communities, or developments in areas that are not priorities for government funding. Other social provision is market-based, sometimes with targeted public subsidies to help equalize the purchasing power or consumer capacity of citizens buying services. For example, the Saskatchewan and Canada income security systems for families, rather than providing goods or services, provide parents with a cash benefit for children’s needs. Almost without exception, parents purchase goods and services for children in private markets, without governments getting involved in supply issues.

Some social needs are simply defined as outside the boundaries of social programs, for reasons of policy, cost to government, or priority. Major sub-sectors of health care, for example, such as prescription drugs or dental needs, are either beyond the scope of public health care or insured under more restrictive or exclusionary rules. In health care many people purchase private supplementary health insurance or receive coverage as a benefit of employment; Saskatchewan also has a system of supplementary or extended health coverage that the provincial government makes available to various categories of low-income people. The choice of program organization or costing model is one that happens in the context of a given time or place, and should not be considered beyond change or reconsideration. Different choices at periods in our social policy history could have resulted in quite different configurations of social programs. For example, national legislation was drafted in 1943 for a contributory, social-insurance style health program, more than two decades before Canada adopted Saskatchewan’s model of a health social utility. It is quite conceivable that some of today’s social programs like unemployment insurance or public health care could change their form or financing arrangements as their economic and social context changes, or as more is learned about effective and sustainable program approaches.

The possibility of change—even quite fundamental change—to social policies and programs should be welcome, despite the inevitable concerns of those involved in the status quo. Social policy is not a new discipline, but that social measures should so effectively dominate the fiscal affairs of government is certainly new. Most of the major instruments of social policy are in their first or second iterations. The emergence of evidence-based and outcomes-oriented approaches to social policy, and the application of concepts such as comparative advantage to social decision-making, promise changes in the coming century at least as profound as in the last.

Angel, S. 2000. Housing Policy Matters: A Global Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Beveridge, W. 1942. Social Insurance and Allied Services. New York: MacMillan.

Canada, Department of Finance. 2005. Total Federal Support for Health, Post-Secondary Education and Social Assistance and Social Services (2004–05). Ottawa: Minister of Finance.

Grauer, A.E. 1939. Public Assistance and Social Insurance: A Study Prepared for the Royal Commission on Dominion-Provincial Relations. Ottawa: The King’s Printer.

Guest, D. 1997. The Emergence of Social Security in Canada. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Inge, P., P. Conceiçâo, K. Le Goulven and R.U. Mendoza (eds.). 2003. Providing Global Public Goods: Managing Globalization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lightman, E. 2003. Social Policy in Canada. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. 1988. Social Policy Studies No. 6: The Future of Social Protection. Paris: OECD.

——. 1994. Social Policy Studies No. 12: New Orientations for Social Policy. Paris: OECD.

Statistics Canada. 2004. Cornerstones of the Community: Highlights of the National Survey of Nonprofit and Voluntary Organizations. Ottawa: Minister of Industry.

Westhues, A. 2003. “An Overview of Social Policy.” Pp. 46–72 in A. Westhues (ed.), Canadian Social Policy: Issues and Perspective. Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

Rick August

Print EntryHOME | BROWSE BY SUBJECT | ENTRY LIST (A-Z) | IMAGE INDEX | CONTRIBUTOR INDEX | ABOUT THE ENCYCLOPEDIA | SPONSORS TERMS OF USE | COPYRIGHT © 2006 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF REGINA | POWERED BY MERCURY CMS |

|||

| This web site was produced with financial assistance provided by Western Economic Diversification Canada and the Government of Saskatchewan. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| Ce site Web a été conçu grâce à l'aide financière de Diversification de l'économie de l'Ouest Canada et le gouvernement de la Saskatchewan. |

|||