Before Saskatchewan was constituted, First Nations people and settlers had already claimed the land with artworks they placed in shared spaces. Today, petroglyphs, religious effigies and monuments that predate the province are routinely encountered by diverse publics. Following this early history, public art in Saskatchewan is most often associated with the memorial: an artifact intended to honour or preserve the memory of a person, an event or an idea. For example, in Gravelbourg, Kamsack and Moosomin, war memorials safeguard the names of soldiers killed in service. They also provide mourners with sites where they can gather and commiserate. In Rama, Esterhazy and Kronau, field stone grottos host cycles of religious statuary. Since 1990, Moose Jaw has sponsored a number of murals celebrating moments from the city's history. In Saskatoon, bronzes of Sir Wilfrid Laurier (1972), of Métis leader Gabriel Dumont (1985), and of former Governor General Ramon Hnatyshyn (1992), all by Bill Epp, root into the land an institutional interpretation of Canada's political history. By sponsoring and facilitating the production of these artworks, governments and communities attempt to create a collective portrait showcasing personalities they admire, values they champion, and memories they treasure. Public art marks a site for remembrance and social ritual.

But public artworks can also be viewed as aesthetic landmarks or symbols of urban regeneration. Indeed, during the 20th century new tendencies in public art emerged. Artists such as John Nugent, Robert Murray and Edward Gibney, more interested in contemporary art practices than in commemoration, installed large-scale abstract sculptures in public places. Alongside this trend appeared site-specific artworks that reflect on their physical and human surroundings. In Regina's Wascana Park, for example, considering the history of the location, Doug Hunter installed Oskana (1989), a collection of bronze bison skulls surrounded by carved stones. For Antsee (2002), Kim Morgan appropriated a decaying tree in the city's Victoria Park and brought it back to life by populating it with a colony of shimmering aluminum ants.

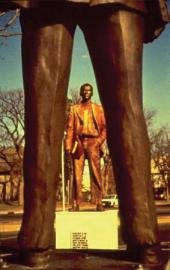

In 1992, Saskatoon-based artist Taras Polataiko presented a bracing critique of the tradition of public art in Saskatchewan. Transfigured into a breathing monument, completely bronzed and hoisted onto a pedestal, the artist installed himself facing the aforementioned monument to Hnatyshyn. Today, Polataiko's performance work only survives in photographs. Yet it still generates crucial questions: about the relationship public art cultivates with sponsors, viewers, and the spaces it inhabits; and about the role public art plays in the selective consolidation of community, the creation of public memory, and the consecration of taste in the public sphere.

Annie Gerin

Print EntryHOME | BROWSE BY SUBJECT | ENTRY LIST (A-Z) | IMAGE INDEX | CONTRIBUTOR INDEX | ABOUT THE ENCYCLOPEDIA | SPONSORS TERMS OF USE | COPYRIGHT © 2006 CANADIAN PLAINS RESEARCH CENTER, UNIVERSITY OF REGINA | POWERED BY MERCURY CMS |

|||

| This web site was produced with financial assistance provided by Western Economic Diversification Canada and the Government of Saskatchewan. |

|||

|

|

|

|

| Ce site Web a été conçu grâce à l'aide financière de Diversification de l'économie de l'Ouest Canada et le gouvernement de la Saskatchewan. |

|||