At the time the province of Saskatchewan was formed, people with intellectual disabilities, then referred to as “mentally retarded,” were treated in the same way as those with psychiatric disabilities. The provincial Mental Health Act of 1936 was the first recognition of a distinction between intellectual deficiency and mental illness. In the mid-20th century it was common to house, educate, and care for people with intellectual disabilities in institutions. In 1947, the Saskatchewan Training School for people with intellectual disabilities opened in Weyburn as a temporary facility, until in 1955 it moved to Moose Jaw, where it is now known as Valley View Centre. By 1961 the Saskatchewan Training School was filled beyond capacity, and a second facility was opened in Prince Albert.

Even in this period of institutionalization, parent groups were beginning to organize to develop educational services for children with intellectual disabilities. In 1955, parents formed the Saskatchewan Association for Retarded Children (now known as Saskatchewan Association for Community Living or SACL), with an initial focus on children's education. Through the 1960s parent groups expanded their focus to include the development of community organizations to support adults with intellectual disabilities. A network of sheltered employment workshops and activity centres, group homes, and developmental centres emerged as communities experimented with alternatives to the institutionalization of people who were labeled mentally retarded.

During the 1950s and 1960s, the federal government increased its financial support to provincial social programs. Among the areas of expansion was the Vocational Rehabilitation of Disabled Persons (VRDP) Act of 1961, which for the first time provided federal cost-sharing to help the province develop programs for people with disabilities that were “rehabilitative” with respect to employment and daily living. In 1968, the Saskatchewan Association of Rehabilitation Centres (SARC) was formed by eight community agencies operating vocational workshops for people with intellectual disabilities. Over the years SARC has expanded its membership and significantly increased the services, supports, and employment opportunities available to people with intellectual disabilities in Saskatchewan communities. One of its most notable achievements is the development of SARCAN Recycling, a substantial non-profit business venture that is now a major employer of Saskatchewan people with disabilities.

An important work by Wolf Wolfensberger (1972), Normalization, was influential on directions for federal and provincial investment, and on how the provincial government organized its services and supports. A single provincial administration was created in 1972 to coordinate and strengthen government health, social service, and education services to people with intellectual disabilities, with a focus on community-based options. During this period, government and community agencies expanded training on the job programs to provide people with disabilities with more opportunities to develop their labour market attachment. By the 1980s, communities had demonstrated significant capacity and willingness to accommodate the needs of people with intellectual disabilities. A trend towards deinstitutionalization was well established, and many people who were previously seen as lifetime residents of institutions were moving into communities. An emerging focus on the potential of each individual resulted in further development of individualized community program options for people with disabilities. In 1985, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms explicitly recognized persons who were mentally retarded as full citizens.

The decade of the 1990s saw continued growth and development of community-based services for people with intellectual disabilities, with a continued focus on supported employment programs and services. There were also advances in research and policy development, and milestones in recognition of people with intellectual disabilities as citizens, workers, and members of communities. As the province enters its second century, our perspective on people with intellectual disabilities continues to evolve. The Disability Action Plan, proposed by the Saskatchewan Council on Disability Issues in 2001, expresses a vision of “a society that recognizes the needs and aspirations of all citizens, respects the right of individuals to self-determination, and provides the resources and supports necessary for full citizenship.” Mainstream service systems are now becoming more inclusive of people with intellectual disabilities.

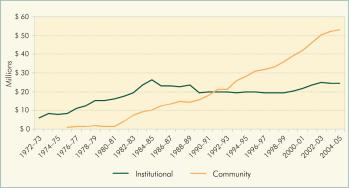

In 1974 there were about 1,200 individuals with significant intellectual disabilities living in institutional settings, compared with approximately 1,400 living in community settings. Twenty years later the estimated number of people with intellectual disabilities living in communities had increased to over 3,200, and the number in institutions had declined to fewer than 400. Trends in institutional versus community living attest to the success of Saskatchewan communities at developing supports for people with intellectual disabilities. (See Figure CSID-1 above.)

James Sanheim